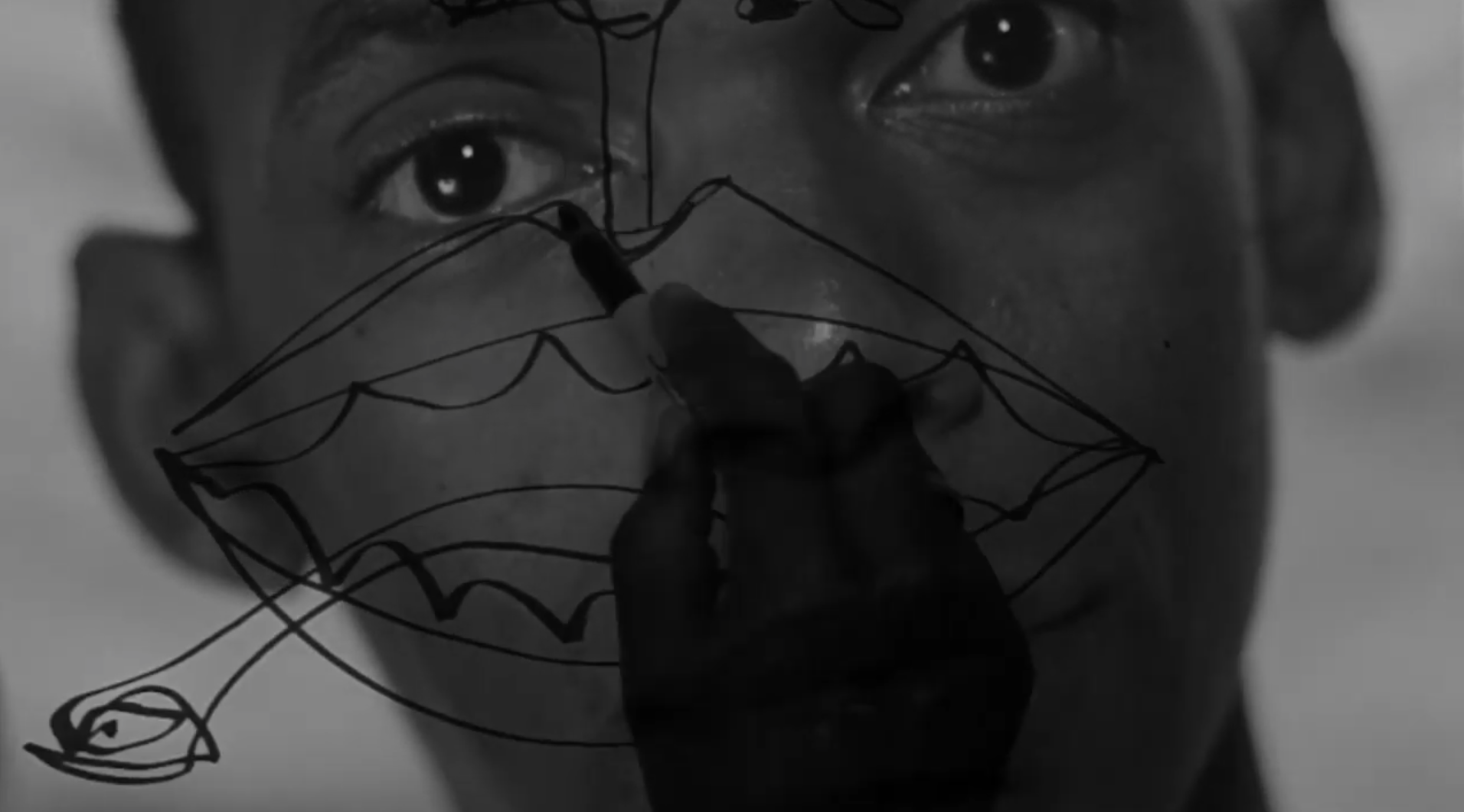

Still from the video installation After Grace: I - VII (2019) written and assembled by Dez’Mon Omega Fair

The 2019 Film and Video Poetry Symposium was our first program with an artist in residence. Poet and performance artist Dez’Mon Omega Fair not only trailblazed a structure for future residencies, but also presented groundbreaking content.

Fair’s videopoetry series “After Grace” was presented at The Los Angeles Center for Digital Art in situ with his piece “At The Cross”, an assemblage of ink on washi paper, poetic text, and found objects spanning a 12 by 12 foot wall for our gallery program “Analog Sun, Digital Moon”.

Visual artist and filmmaker Avital Oehler interviewed Dez’Mon about the creative process for both his poetry and work as a painter. The following exchange between the artists began on May 17, 2019 and ended June 29, 2019. This article was edited then finalized on June 19, 2020.

Avital Oehler: Talk about the poem After Grace. Is it self-referential? Is it borne out of our culture’s obsession with social media?

Dez’Mon Omega Fair: After Grace is about coming into deeper self-awareness. The poem is also about three different views of the same experience. It is a kaleidoscopic vision coming into focus. Finally. Or maybe. A complete feeling in reflection. This poem marks my decision to identify as a writer and poet. Writing for me, is an attempt to articulate the act of painting. After Grace signifies the transition from watercolor to poetry. And now poetry to installations, from there to performance.

Avital Oehler: How did the poem After Grace become a video project?

Dez’Mon Omega Fair: After Grace kept repeating in my mind as various lines, in various rhythms, allowing me various vantage points. Growing louder as I continued forward through several life transformations. Rumination did not stop until I wrote the words down. The videopoetry medium emerged from me quickly after.

I not only arrived in Los Angeles anticipating new experiences, but I had also left a familiar creative practice on the east coast. I no longer had a studio. I had my paintings but no longer had the space to physically express myself, to make the mess of visual art. Videopoetry became a way to continue practice with a visual space, looping in collaboration with artists I value.

Avital Oehler: How did you choose the video directors?

Dez’Mon Omega Fair: The filmmakers and I chose each other. Particularly, two of the directors I had worked with over the years in fashion. I did the costumes for Kailee McGee’s feature length film #Blessed (2015). In this way, we had already developed our joint aesthetic and work ethic. Lior Shamiz and I met during a residency at PAM Residencies. In a studio visit I shared with them the project. Lior’s film was the sixth version of After Grace.

Poetry uses language to surmount itself. I hope the viewer gets a sense that poetry is everywhere and all moments are an entry point. And the experiences with these creative people come from a realm much larger than purposeful friendship, networking, or choice; each person I encounter creatively, merely continues the ongoing reflective quality that is Art.

Avital Oehler: What instructions, if any, were given to each filmmaker?

Dez’Mon Omega Fair: After Grace as a videopoetry series has been and continues to be a work in progress, instruction varies, and converges with the filmmakers where they are in their own practice. Camille Cotteverte, for example, was excited and primed to use a cinemagraph effect and felt that a controlled environment would suit best. I had completed an iteration of a work titled At The Cross, an immersive installation of large watercolors and other source materials at PAM Residencies. This was the perfect environment for her to video experiment. Camille presents her interpretation of After Grace as documentation of my work at PAM gallery space. Another collaborator, David Andrews was searching for projects that were less advertisement driven and more artful. We hybridized the poem with a commercial framework: “To sell poetics”.

Image from the videopoem After Grace: IIX (2019) directed by David Lockwood Andrews

Avital Oehler: Talk about the experience of making videopoems.

Dez’Mon Omega Fair: One has to want to. Filmmaking certainly has not proven to be as forgiving as painting or writing for me. So I stay away from the production cycle if I can. I place my energy more so into the continuous mission to make sure that the filmmakers have a destination for their films.

Avital Oehler: Was it a collaborative effort?

Dez’Mon Omega Fair: Good collaborative work is all about trust and good collaborative work is also about tension. But most importantly, one has to want to see the other succeed. Having a different perspective is the point of collaboration in my opinion. But overall, the collective vision requires both artists to respect what brought them together. Further, to be known, seen and or challenged by another person in creative space, a vulnerable space: This is where the beauty, and or chaos of making work with others can thrive.

Avital Oehler: Poets, filmmakers, and artists are legendary for being controlling. Did you discover yourself within a power dynamic or struggle while collaborating?

Dez’Mon Omega Fair: I did, though; this tug of war is futile. A tug between three: what I thought the project was; what the collaboration efforts should be; and the reality of getting it done, all began to remind me of past lessons with watercolor.

Releasing the illusion of control is my only way to consciously paint with water: acceptance, mutual decisions, and impressions. Working with others becomes working with water; I’m in conversation with the science and the nature of a person, with the science and nature of an environment. All of existence is collaborative. A happy medium can be maintained between what you want and what’s happening in the moment. I live in this division.

Avital Oehler: What did you intend to accomplish with these films and the After Grace project?

Dez’Mon Omega Fair: Repetition. Maybe even exercising some boredom and out of boredom comes something else. I intend the project to feel like it does when you hear a pop song on the radio too often, and then remixes come.

I also took the cue from who I was in the company of. I surrounded myself with performance artists, namely my partner, Nick Duran and other brilliant artists who are technically strong and emotionally raw in their practice, their expression. I became a part of a community of artists at Pieter Performance Space in Lincoln Hieghts, Ca. Seeing more performance art while collecting video content, I began to feel more clearly that all people are artists but we so easily forget. We need to be reminded over and over again. To instigate this idea I decided to repeat the same poem over and over again within my performances. Thinking perhaps at some point my poetry will become propaganda for a more aspirational future. Poetry and visual art needs to be propagandized: agitprop. I’m here for it, for expressions that invoke “non-artist” into new avenues of creative thinking.

Still image from the videopoem After Grace: VII (2019) directed by Jonathan Fasulo

Avital Oehler: Is there a film that stands out in your mind? For me, Fasulo’s film touched me on a deep visceral level that I can’t even quite explain.

Dez’Mon Omega Fair: Jonathan Fasulo’s piece After Grace: VII (2019) is an example of major shifts in how African men are seen, portrayed, and embodied in film. Narrow and pejorative narratives of the past are being evened out. I think about the evolution of black queerness in popular culture: RuPaul, slowly for decades, now successfully carving out space for the art of drag in the mainstream; Billy Porter in Pose; and Frank Ocean an obsession among everyone, but especially straight men. Yah know.

From the After Grace: VII shot list: [back bending over waves and jagged rocks in a pseudo sports illustrated poetry flick] this is Jon and I’s friendship and working relationship in a nutshell. Jonathan has been taking my photo for years, since we were twenty something young at Savannah College of Art and Design.

Avital Oehler: Are more films forthcoming?

Dez’Mon Omega Fair: Yes, there are multiple videopoems in post. I also have a new After Grace stanza.

Avital Oehler: Some of the videopoems focus on you, while others focus on your artworks. Say a few words about your approached to either of these elements.

Dez’Mon Omega Fair: Most of the filmmakers wanted my personhood at center though I was influencing them to find something to shoot without me, from within themselves; that proved not so readily imaginable. I had to become “okay” with taking up more face time, requiring me to develop my own senses for performance and with this I often brought along my visual artwork. Doing so is uncomfortable but important educationally. I further understand what my personhood represents in the world because of my participation in the work. This ushered in ownership of said messaging and identity.

During the development of After Grace II (2015) filmmaker Sarah Harron wanted to film the painting process. We went with a parallel message of incomplete works, works in progress, that is, since this was only the second videopoem in the series, I was still unsure about where the overall project was going. It was still being painted, filmed, collected, pondered upon, etc. When we completed the takes, Sarah edited the footage together with silence, adding motion text, the stanzas of the poem floating juxtaposed to the motion of my brush and sponge. This iteration is about further contemplation: waiting for the right moment to add new elements.

These videopoems have also become a chronicle of not only the shifts within my practice, but also my ongoing development as an artist and writer. Archiving my artwork in this manner was not a deliberate function for After Grace. Though I am pleased with the project being a marker that indicates such evolution for myself. Through this I have learned to exercise keeping an historical record of my work and I have been grateful for the filmmakers for this as well.

The shift into performance is almost too raw to chew on, to talk about. I can say that I’ve noticed new forms of serendipity while producing videopoems. Opportunities arise to travel deeper into vulnerability, to practice spontaneity, and be on the look out for happy coincidences. These are invitations to acknowledge my intuition so that I may maximize an effect. For example, the poem for Camille’s piece was recorded in the middle of the Integratron. This is a 38 ft tall cupola structure with a diameter of 55 ft designed by ufologist and contactee George Van Tassel. Tassel built the structure in Landers, California, supposedly following instructions provided by visitors from the planet Venus. I made the recording after a sound bath because the facilitator suggested trying the acoustic resonance.

Director Lior Shamriz brought the series through a much different threshold. I invited them to the project as they were completing another film abroad with artists Chloé Griffin, Jongwook Choi, and Yoji Matsumara. Lior filmed After Grace: VI (2019) in rural Japan. I am absent from the set.

Threshold II (2011) watercolor on washi paper by Dez’Mon Omega Fair | Photographed by Ward Price

Avital Oehler: Is there a specific meaning of the painted pieces as they relate to the poem?

Dez’Mon Omega Fair: No. But, the paintings and the poem share a goal or a utility. Both share teams of thought and work in tandem to create a flow state, meditation, or groove. This “groove” is fairly accessible to me when I’m painting. Not so much for me with writing.

The act of speaking, reading, or writing words is fickle in a way that the pigment, line, and shape are not. Firstly, language can be of a different place, time, or culture. I have also recognized that images are forever logged in the subconscious mind while words are forever changing or fade. Because of this I activate poetry as a marker on my current and linear timeline, for this case it is my painted images.

I am asking the audience to find within themselves perhaps the place where I am writing from, to rework their ideals of language from the inside to the outside, while also maintaining a memory of how these concepts are reduced to the spoken word.

Avital Oehler: You have amassed quite a treasure trove of these watercolor paintings — how would you like to present them to the world?

Dez’Mon Omega Fair: In mass, covering an entire gallery space has been satisfying. I have had ceremoniously long and private showings of watercolor, presenting them one by one equaling hundreds or so. It can be exhausting, but is also gratifying and soothing. My practice is one of catharsis.

I’m most happy with my exhibitions when they achieve a sense of ceremony or even church. My favorite exhibit so far was in Pendleton Center for the Arts in Oregon. In performance, the audience and I hung the show as I presented Novel Sonics. This is an experience I have crafted that explores the use of long-form soundscape, audio recordings of riddles, prose, poems and chants. During the performance there was a flash thunderstorm. The attendance was small. By the end of the storm, by the end of the recording, we were surrounded by a completed show.

Brainstorms I have for future installations include large freestanding glass frames, where two watercolors are set back to back, arranged so the washi paper may become transparent yet remain vibrant within sunlight. I’d like to create mazes of large watercolor paintings. Reupholstering vintage sofas in watercolor silk, then sealing them in plastic. I’m also designing ways of integrating sound installations of poetry in public spaces.

Avital Oehler: What was your motivation to create with watercolor?

Dez’Mon Omega Fair: A personal need was my motivation to paint. When one draws, writes or paints it should be understood that you are, in fact creating new neurological pathways in your brain. Your brain is also mirroring your thinking back to you within the works created. I hadn’t worked with my creativity in such a way before discovering that art making is also self-help. In addition, and quite simply, I wanted to work with water. Working with elements was a welcomed conundrum. Water can be solid. Water is a liquid, a gas. It sustains life. It is aware and that awareness implements its own memory. Working with water, as I may have said before, feels more like collaboration with some primordial intelligence.

Avital Oehler: I love how the washi crinkles and pulls under the weight of the watercolors. Is there significance to that or just a happy coincidence?

Dez’Mon Omega Fair: In basic terms, Washi means traditional Japanese paper, wa (和) meaning Japanese and shi (紙) meaning paper. Made using the inner bark of the gampi tree, mulberry, or the mitsumata shrub. The inner bark being the eldest part of the plant. I’m not sure how much significance this holds, but I think to consider it.

Avital Oehler: What is your artistic process in the medium of watercolor?

Dez’Mon Omega Fair: My work with water on washi is an intuited pictorial conversation abstracted from the heart, impressions of aself emerging from the history of the body. Painting is focused on understanding art-making as a universal language attuned to an elevated intuition, embodying the present, reorganizing the past, to fine-tune, creating what is possible.

Materially, my work consists of water, liquid watercolor on various weights and scales of washi. I do, but rarely use brushes. With watercolor/ink, I’ll enter pre-wet regions, or inking dry, bringing in afterward sprayed water to activate chemical changes.

The vibrant interlocking of the water and the immediate travel and spray of colors blending into the fibers is innumerable; using stencils, book corners, shoes, eyeglasses, (anything in my grasp) to create familiarity, while water comes in to blur, enhance, or rework shapes anew. The diaphanous, yet strong washi converges the density of liquid watercolor creating polarizing effects: a polychromatic assemblage of complicated line work unraveling.

Using time as medium, adding and mimicking, never subtracting or hiding what could be considered ill or err. Paintings ten at a time, stacking, rotating as they bleed into each other; creating a machineless print make like routine, baring a string of like and unlike imagery.

My watercolor oeuvre averages a scale of 25in x 37in. Mostly of my easel, a found piece of wood: curved, thinly layered rectangular cut imbibes seven years of watercolor and mothering over four hundred works thus far. Water applied to the wood reconstitutes the watercolor left in the board to spawn motifs, so new work is made from remains of a past painting, having an identity, amassing a conversation of its own; culminating into an image that is close to what I had imagined or more discursive in ways that I continue to perplex. Past becomes present, that is, implication of present becomes future. Galvanized by this meditation: the release of judgment to comprehend newly; understanding in renewal, what’s always been. Utilizing the patterns, synchronicity and symmetry experienced when painting with water: this ethos appears to me. I find that a painting will paint itself, as a life will live.

Image from “When my life hands you Rehab, Help Yourself: A Novel Sonic” (2019) performed at Pieter Performance Space

Avital Oehler: Your watercolor creations look at us, address us, or insist on us seeing them. Are directness and honesty something you aim for in your work?

Dez’Mon Omega Fair: Southerners say, “If it was a snake it would have bit you!” when you find something you’re looking for that was very close to you, that was right under your nose. I wish I had started practicing art seriously earlier in life. I know it’s pointless to hobbyhorse the thought, but the directness you’re suggesting might actually be a feeling of, at last. Kismet. I, in fact, did get bitten by the snake and have been getting the urge to paint more as I’ve gone on producing these films.

Avital Oehler: Are there other mediums you’d like to explore?

Dez’Mon Omega Fair: I think I’m good on exploring mediums for now. Leaning more deeply into what’s happening as all the current mediums come into better concert with one another. For instance, I’m hosting a listening party slash performance; slash kick back, where we’ll do some group creative meditations, a small happening in preparation for the symposium. I’ll recite poems and some people will draw and some will drink and be drawn. We’ll write and dance, who knows what other mediums may arrive. If anything, I’m looking forward to discovering and also activating new elements within performance, a way to encourage the audience to participate, but further hoping they leave with some new reckoning about the potential for art within themselves.

Avital Oehler: How did you start your art practice? What was your artistic coming of age?

Dez’Mon Omega Fair: I’m still coming of age in this. I have a lot to learn. That being said, it was arrogance that started my art practice. After leaving respected galleries underwhelmed I started challenging myself to make work that was “better”, to define art, fine art, good art for myself. And like a bunny into a forest of hunters, my ego was shot up quickly, skinned, eaten, and repurposed. I have learned there is no such thing as “better” but there is honesty. Art making is inherently therapeutic. I had nary an idea of the dynamics that would emerge from me and change me from the inside out. The whole of my art practice has become a nine yearlong session of expressive art therapy.

Avital Oehler: What serves as a reference to your work?

Dez’Mon Omega Fair: Recently, I’ve been turning to religious iconography. More so imagery of the Black Madonna. She’s said to represent the human soul and resilience and I love that: first female consciously creating life, holding the young male; he is Her will to survive and is naught, without Her. Creation: She returns, though She never left. I experience endless poetry in these images. I have also been listening to lectures by Stephanie Georgieff who wrote The Black Madonna: Mysterious Soul Companion.

Avital Oehler: What are some of your musical influences?

Dez’Mon Omega Fair: I’ve been listening to Klein, and the songs Slipping and Prologue, on repeat lately. These are off the album Tommy. Her mixes are trance inducing with syncopated frenetic sounds that soothe, however guttural.

Avital Oehler: Your work spans across mediums. Including film, body-based performance, voice-based performance, and watercolor. Is there a theme that connects them, or are they standalone?

Dez’Mon Omega Fair: I think you’re not supposed to say this, but I believe in beauty. I look for it. I try to achieve it. In my painting I wait for the stopping point, on beauty, where the more sparse paintings hush me by screaming, Back off! Beauty becomes a striking and illusive serendipity, unlike the body which is as ephemeral but from which we perform our existence.

[END OF DIALOGUE]

Avital Oehler conducted and collected this dialogue with Dez’Mon Omega Fair. She is a self-taught photographer, filmmaker, and writer. Oehler earned her Master’s degree in Forensic Psychology, worked in academia, prisons, and with law enforcement before transitioning to visual art and filmmaking. Her practice lies somewhere between documentary and fiction, toying with notions of reality and place. Oehler’s portfolio is available for review at www.talyoehler.com.

Dez’Mon Omega Fair is an interdisciplinary artist and poet living in Long Beach, California. Fair’s work explores self-reflection, behavioral observation, and the cathartic achieved through brushless ink on traditional Japanese paper, collaborative videopoetry projects, and experimental forms of poetry. He is pioneering a genre he has titled ‘Novel Sonic’, which implores the use of long form audio recordings of poetry readings, large-scale immersive installations, and large-scale performance.

You may view selections of Dez’Mon Omega Fair’s portfolio by going to his website: www.dezmonomegafair.com. Fair’s videopoetry series After Grace (2019) was presented daily as part of a public exhibit titled Analogue Sun, Digital Moon at The Los Angeles Center for Digital Art. His installation titled At The Cross (2019) was also presented within the same show. This exhibition ran July 11, 2019 thru Aug. 4, 2019 as part of The 2019 Film and Video Poetry Symposium. Click here for the full 2019 Symposium program.

A .PDF file of this article is available here or within the FVPS digital archive.